When I began my career in football analytics in 2017 I felt like a good place to start would be to the work already done in that area. I dug into any publicly available research I could find, but sadly this was before the NFL started the Big Data Bowl, before nflscrapR and cfbscrapR, and before the explosion of work done by amazing analysts on Twitter.

Though there wasn’t a lot out there, there were still some gems, one of which was Bill Connelly’s amazing piece on the five factors of college football. If you have not read it yet, stop reading this and go read it here immediately (and then come back and finish). This truly helped shape my views on and guide my exploration of football stats and analytics.

The five factors that Bill talks about in his article are:

- Explosiveness

- Efficiency

- Field Position

- Finishing Drives

- Turnovers

These are the most important aspects of football. Explosiveness is listed first because it is the most impactful on wins and losses. Because of that, I wanted to talk about explosiveness, more specifically, explosive pass plays.

There are many definitions one can use to define explosive plays. 12-yard runs? 15-yard passes? Plays with EPA >= .8 or 1 or some other cutoff? Each has its merits. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to use plays which go for 15+ yard definition for passes as a cutoff in order to examine how StatsBomb data can help teams utilize data to build a more explosive offense.

All stats below are using data from the 2021 season across the NFL and a selection of FBS competitions.

Offensive formation width

An initial offensive formation is the first thing to investigate on every play. “Reduced” formations, with receivers tucked in closer to the offensive line, have become very popular in the NFL. There are a few reasons for this, but the virtue of this approach is that it is more difficult for defenders to “press” or jam the receivers at the line while also opening up a lot of horizontal space for out-breaking routes.

In such narrow formations, the receivers are often stacked, or aligned in bunches. This puts added stress on defenders as it forces more communication, and increased chaos to sort through.

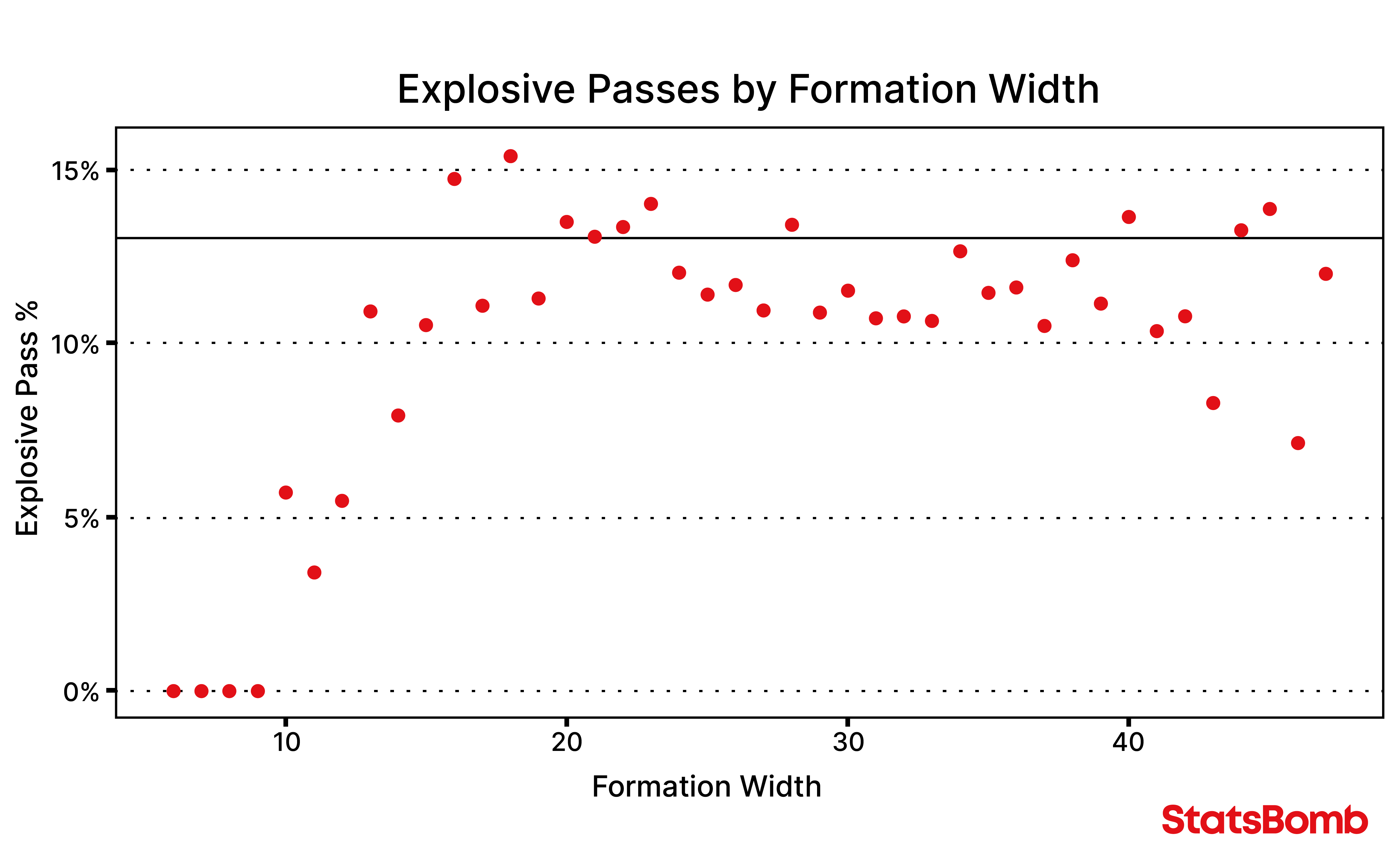

The above diagram shows the explosive pass percentage (y-axis) by formation width at snap (x-axis). The reference line highlights the 10 “most explosive” formation widths. There is a cluster of highly explosive formation widths around 20 yards, with the most explosive formation width at 18 yards. The width of an offensive line is about 7 yards on an average play, so this gives about 11 yards for the rest of the receivers to line up in, or 5.5 yards on either side of the tackle in a balanced formation.

The formation width with the fourth highest percentage of explosive passes is at 45 yards. As the field is 53 ⅓ yards wide, this allows only 8 yards total outside the widest offensive players to either side. These spread-out formations are very popular in college football, with the main idea of stretching the defense, forcing them to cover the entire width of the field. This allows for more one-on-one matchups, as the large distances make it more difficult for safeties to help on outside receivers.

Pre-snap motion

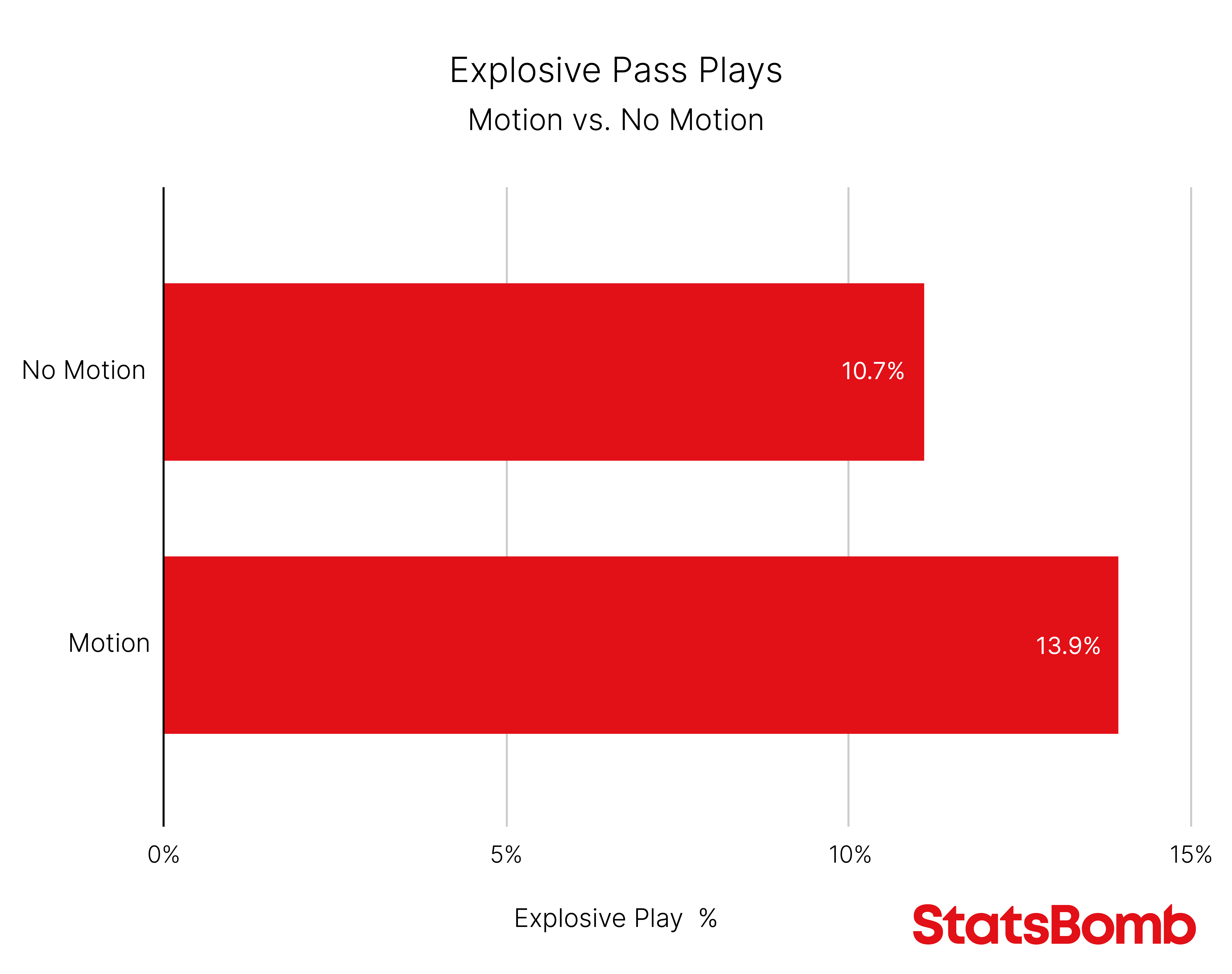

Even before the ball is snapped, there is another thing the offense has control over, motion. Motion has multiple purposes from identifying coverages to creating opportunities for confusion and miscommunication for the defense to creating specific favorable matchups. At least in terms of setting up explosive plays, motion has substantial benefits.

With the margin being so thin between winning and losing, any possible advantage is worth utilizing. In that context, achieving three extra explosive plays per 100 attempts is a significant edge!

Play Action

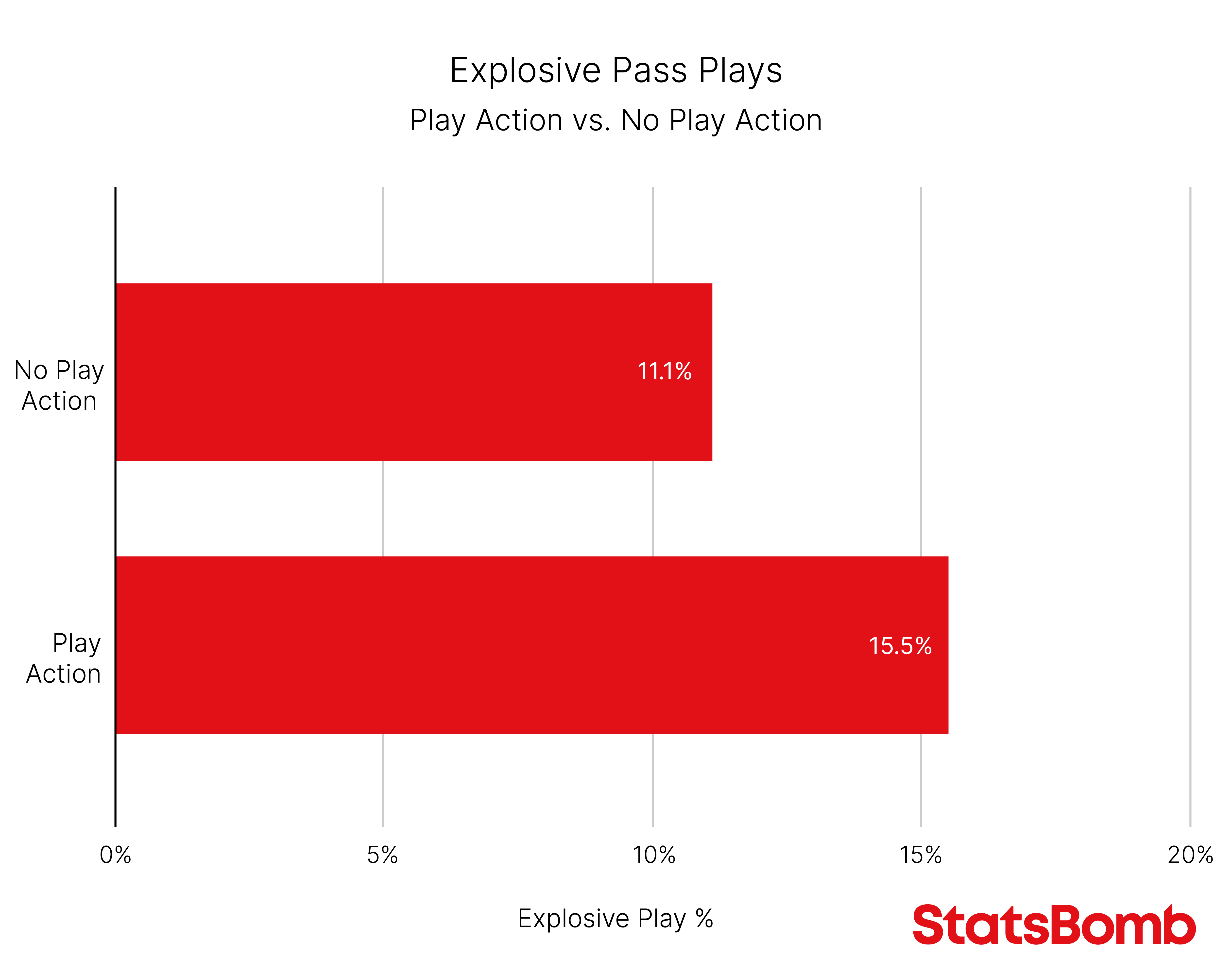

Another important source of misdirection comes after the snap: play action. Conventional wisdom suggests play action makes a passing game more effective. At least in the context of generating explosive gains, that hypothesis appears well supported.

Target Area

All the setup in the world only matters so much. You still have to throw and catch the ball, and where the ball is thrown has a tremendous effect on the likelihood of a big play. For example, A go route is far more likely to turn into a chunk of yardage than a 2-yard hitch.

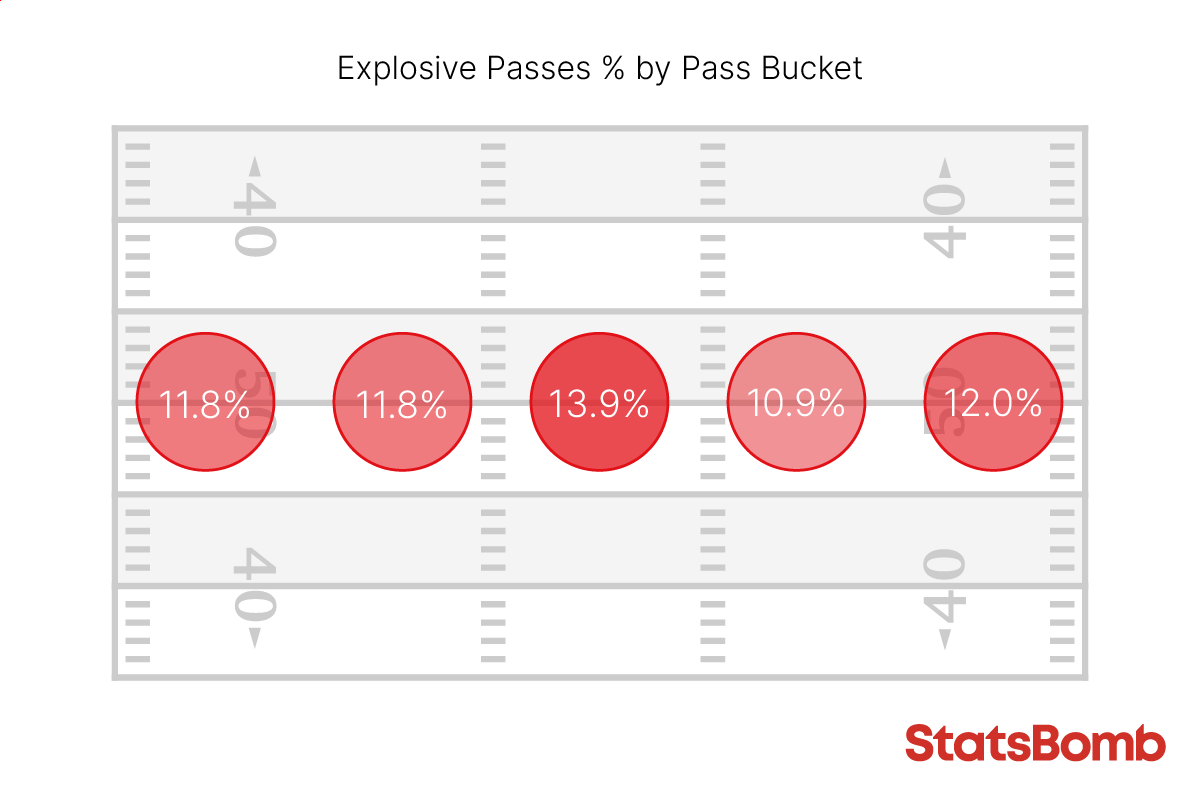

For this analysis, I wanted to get a good feel for both where the ball is thrown horizontally and vertically. Let’s start with looking at where on the field horizontally the ball is thrown. First, I divided the field into five zones from left to right: from each sideline to the numbers, from the numbers to the hash, and the middle of the field (between the hashes).

Wide areas outside the numbers on either side had very similar explosive pass percentages with these routes consisting mostly of fades, corners, and deep comebacks. Working in from the sideline areas, the area from the left hash to the numbers had a very similar percentage as outside the numbers. The area from the right hash to the numbers was noticeably lower than the rest. The middle of the field had the highest percentage of explosive passes. In this era of football with all the rules in place protecting offensive players from big hits over the middle of the field, it has never been more imperative for offenses to attack defenses in that area.

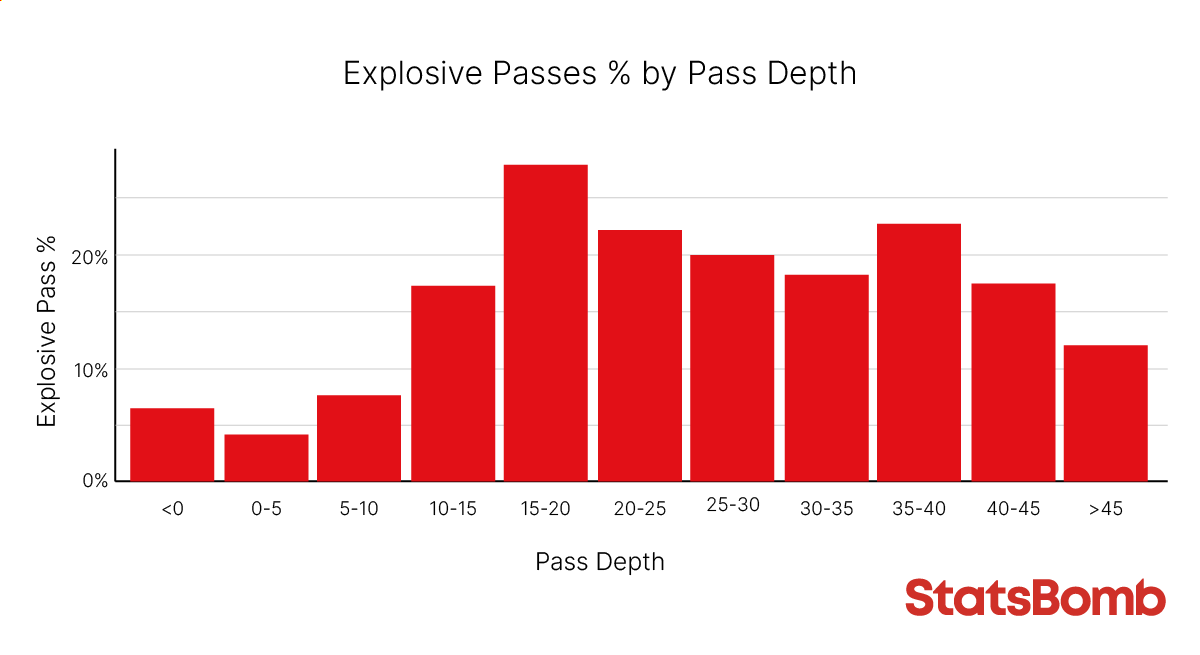

Moving on to pass depths, unsurprisingly, short passes don’t lead to explosive plays as often as longer ones. But the optimal strategy is not just to throw it deep and watch the explosive plays pile up. The passes producing the most frequent explosive gains target an area between 15 and 20 yards downfield - deep enough to be large gains when they are complete, but short enough that they still have a high likelihood of completion.

Putting this all together it’s easy to ask why don’t teams just run all their passes with play action, from a condensed formation, with some pre-snap motion, and throw the ball between the hashes 15 to 20 yards downfield? Football sadly does not work like that, but each of these insights are aspects that can be useful for coaches to keep in mind as they put a well-rounded plan of attack together. Focusing on explosive plays in and of itself will not make teams more explosive, focusing on what actually leads to explosive plays will.

Matthew Edwards

Head of American Football Analysis

@thecoachedwards